Who

Visiting Charleston, South Carolina? Take the Grimke sisters tour!

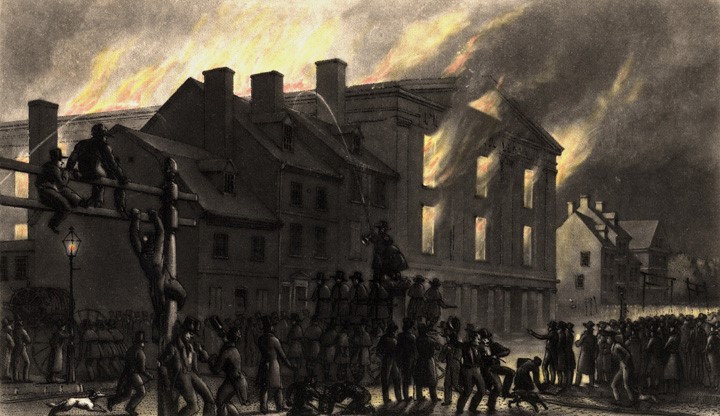

Read about the Grimke family home in Charleston. |

About the SistersBorn near the turn of the 19th century, Sarah and Angelina Grimké were white Southern aristocrats of Charleston, South Carolina whose fate at birth seem sealed: by rights they should have married well, mothered many children and managed the slaves who ran their households. Instead, they rejected slavery, which they hated, moved to Philadelphia, and converted to Quakerism, wrongly supposing that it continued to embrace the cause of antislavery. In time, rejected by the Quakers for their reform work, the sisters became social activists in the causes of abolition and ending racial prejudice. Making the principle that no man should have dominion over another man their own, they became the first American women to make a fully developed case against the oppression of women and for women's equal rights.

Sarah Grimké (1792-1873) Sarah, the older sister, had a scholar's bent, with a judicious mind. Once she established her carefully arrived at conclusions, she never budged, regardless of the consequences. A deeply spiritual person, she was the more tender-hearted of the two sisters. Older by 13 years, Sarah devoted herself to Angelina's care and education to such a degree that Angelina called her "mother" until she reached her twenties. One of the fascinating stories in the book is that of Angelina's influence on Sarah, her beloved and admired sister, at a crucial turning point in their lives. Sarah turned down two marriage proposals, her ambition being aimed in a more unusual direction - that of being a Quaker minister. Sarah was a moderately skilled speaker but her brilliant mind (she had aspired to be a judge, like their father) produced some of the strongest arguments for women's rights ever penned in her Letters on the Equality of the Sexes (1837/1838). She also published a moving pamphlet appealing to Christian ministers of the south to oppose slavery (1837). In 1838, she went to live with the newly married Angelina in Fort Lee, New Jersey, helped raise three children, taught in the schools Angelina and her husband Theodore Weld founded, and continued to engage in social action -- particularly the growing women's rights movement of the 1850s, though rarely in person. |

Radio Interviews about the Grimkés

On November 4, 2013, Roy Scott of South Carolina Educational Radio did a program about the Grimkes for his "Your Day Radio Program." In this 15-minute interview with me on his "Your Day" Radio Program of South Carolina Educational Radio, I talk about who the sisters are and why their story needs to be told.

On September 28, 2013, host Robin Morgan interviewed me about the book I am writing about the Grimkés and the Boston "How Women Become Political" event (see below) on weekly Women's Media Center Live radio program. Angelina Grimké Weld (1805-1879)

Angelina was by instinct a woman of action, and a natural prosecutor, ready to make a forceful case. Compelled by her hunger for the truth, she possessed great courage in the face of condemnation. Though a gentle personality, she was also a passionate speaker who could command audiences of thousands with the force of her arguments and her unmatched eloquence. She published an appeal to (white) Christian women of the south to petition state legislatures to end slavery, and an appeal to white and black women of the north to join the abolitionist cause. She also was the first American woman to address a legislative body. The opening of her speech, in support of abolitionist petitions to the Massachusetts state legislature, is posted on this website under "Long form blog." (LINK). When she was 33 years old, and at the peak of her fame as a public speaker and organizer, Angelina Grimké married the nation's most prominent abolitionist speaker and organizer, Theodore Weld. Now Angelina Grimké Weld, she and her sister lived with Theodore for the rest of their lives. They raised three children, founded and taught in many schools, and continued to engage in social action, although in less frequent and less prominent ways. In 2013, the PBS program, "American Experience," featured Angelina in two of its three episodes in its "Abolitionists" series. |

What about Those Famous Pictures of the Sisters?

The images to the left (Sarah on top, Angelina below) are widely used, both in books and on the internet. The reason is that for many years they were the only images available. Furthermore, they appear to be of the period when the sisters were active in social change campaigns. The two photos at the top of this website page, less frequently published, were taken when they were much older.

But there is a problem with these images. First of all, although they are frequently described as "photographs," they are not. They are not even daguerreotypes. Rather they are wood engravings based on daguerreotypes that have since disappeared. Thus the first question to ask about these images is -- Are they accurate as representations? The answer, obviously, is no. Indeed, while I have yet to track down where these engravings were first published, it is very likely they appeared first in a periodical of the 1830s that disapproved of the sisters for being abolitionists and wished to portray them as peculiar and unappealing. This was a common practice of the time -- to draw people as ugly if you disapproved of their politics or, in the case of African Americans, of their race. I see these engravings more as political cartoons than as legitimate representations of the sisters. |